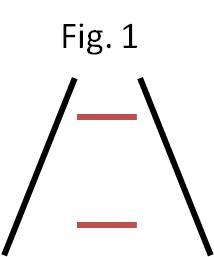

Accumulated experience seems to be the most logical explanation of the “anomalies” in visual perception that we observe. It explains the outcome of perception, but it doesn’t explain the exact mechanism of each “anomaly” that takes place in our brain in order to construct a final perceived image (at the end of the essay we will see that these effects are not “anomalies” at all). Such an “anomaly” in visual perception is “The Ponzo effect”, where the upper red line looks longer than the lower one, despite the fact that both lines are equal in length (Fig. 1).

A plausible explanation could be that our accumulated experience leads us to see this image as a whole and not partially. It is a fact that if we keep only the two red lines the effect doesn’t exist anymore (Fig. 2).

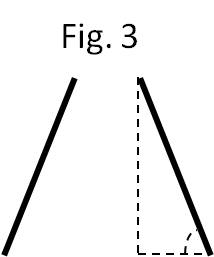

So, what is the mechanism that causes the effect? In order to give an explanation we should examine all parts of the Fig.1 one by one. The red lines are horizontal (they make a right angle towards our orientation) and from Euclidian Geometry we know that a line has only length and no height and breadth, so they are one-dimensional objects. The black lines however, even though they are just lines too, are perceived as two-dimensional objects due to the fact that their orientation towards our point of view makes an acute angle (Fig.3). As a result, in the case of the black lines we perceive both length and height.

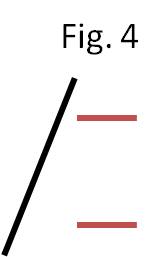

If we combine the two red lines with only one of the black lines, then there will be no difference in the perceived length of the red lines and we may suspect that the reason for the absence of the effect is that this particular combination doesn’t represent a perceived finite topological space as in Fig. 1 but an infinite one, since the right part of the image is “open” and we can’t determine a specific end (Fig. 4).

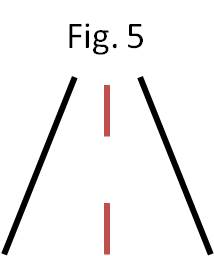

So far, there is nothing abnormal but the things are getting complicated when we combine all lines together as in Fig 1. An explanation for “The Ponzo effect” could be that our brain tries to combine the one-dimensional objects with the two-dimensional objects and extract a three-dimensional image with length, height and breadth. This “mix” of different dimensions and the presence of a perceived finite topological space could be the reason for this effect. In order to test this explanation we will make two experimental steps. The first step is to replace the horizontal red lines with vertical ones because both are one-dimensional objects and make right angle towards our point of view. This is an essential process in order to affirm that the “mix” of different dimensions in an image with a perceived finite topological space is a plausible cause of the effect (Fig. 5).

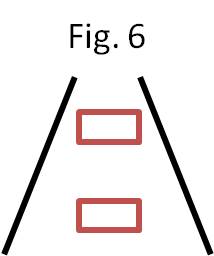

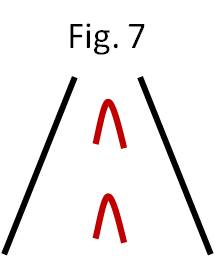

Most people perceive a slight difference in the heights of the two red lines but not as big as they perceive the difference in lengths as in Fig. 1. This time the lower line seems taller than the upper one. The first experimental step confirms our explanation but we need another one step to complete the experiment. We are going to replace the one-dimensional objects (the red lines) with two-dimensional objects (squares or curves) and see if the effect still exists (Fig. 6 & Fig.7).

If we look the image at eye level, then we will see no difference in the perception of the squares’ or curves’ sizes (looking all the images at eye level has great importance). Therefore, our experiment confirms (at least at this stage) the hypothesis that if an image contains objects with different dimensions in a finite topological space causes a different perception of the reality.

If this hypothesis is correct then we can make the conclusion that our brain does not consider one-dimensional objects as normal in a finite topological space (our sight covers only finite spaces and not infinite ones), so it tries to change the image in a coherent way and the easiest and quickest way is accumulated experience. Our brain knows that in physical world there are not one-dimensional objects and when it sees one it understands that it is does not exist in reality.

Photos and drawings are not the reality but they represent the reality, therefore we might say that in our case there are not anomalies in visual perception, but in our thinking. We forget that the reason of drawing pictures and taking photos of the physical world is to represent it and our brain works perfectly in that way. It would be a strange thing and we should be worried if we only perceived lines and curves without trying to find their true meaning and their real purpose in an image. The impact of this hypothesis on the concepts of visual perception is that we shouldn’t try to find defaults in our visual perception but the factors that make our brain so successful in the physical world.

Vision is just one of our senses and our brain combines information from all of them in order to perceive an image in the right way. We have to consider the possibility that the inverse problem in visual perception is not the real problem but the “reverse problem” in our way of thinking.

Stratos A.